CRÓNICA SONORA

Read the original version, in Spanish, here.

Hermosillo, Sonora

You might not know that Plutarco Elías Calles [Mexico’s president from 1924 to 1928], began his tenure as governor of these fertile lands with Decree Number 1, issued on August 8, 1915, which states that, “The import, sale, and manufacture of intoxicating beverages are absolutely prohibited in the state of Sonora.” Offenders could expect five years in prison, while accomplices would get three, and accessories, two. (Archivo General del Estado de Sonora, File 3045.)

Rascals

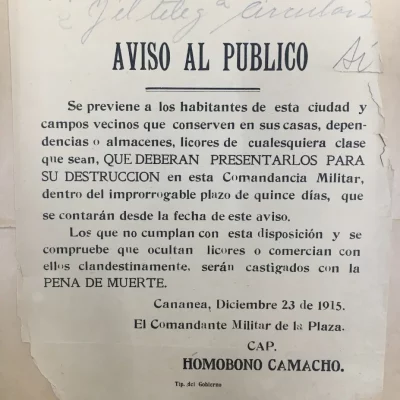

Many of us have already heard or read about the violence of the years during the Mexican Revolution [1910 to 1921] and, given the timorous and prudish way in which Sonorans face events today, such as Covid-19, one might think that they would have immediately fallen in line with the so-called Dry Law. This was not the case, however, and even the mere posting of “public notices” on the walls in the city of Cananea was met with objections. Take a look at the notice below and you might understand why:

PUBLIC NOTICE

Residents of this city and surrounding areas who keep in their homes, establishments, or storehouses liquor of any kind are hereby warned that THEY MUST SURRENDER THEM TO BE DESTROYED by the military command within fifteen days, starting from the date of this notice.

Those not complying with this provision who are found to be hiding or trading liquors clandestinely will be punished with the DEATH PENALTY.

Cananea, December 23, 1915

Military commander in charge

Captain

HOMOBONO CAMACHO

The military, the enforcer of this decree, was actually the first group to violate it, in December 1915. “The Executive has become aware,” wrote the Secretary of State, “that some military personnel, mostly officers of the General Staff, violated the provisions issued on the prohibition of intoxicating beverages, consuming them in the streets, squares and other public places.” In response to this, the second in command to the military commander of the Hermosillo garrison stated, “I believe that those responsible should be apprehended, whatever their political or military rank, and turned over to the competent authorities” (AGES, 3045).

The credibility of military or civil authorities was, nevertheless, minimal. The hypocrisy and impunity were so great that in the same Cananea where the death penalty was promised to those who broke the law, their own secretary of the city council often strolled about drunkenly, in public, as noted in June 1916 by the state’s sub-inspector of alcoholic beverages, in an official letter addressed to the governor [AGES, 3061]. To make matters worse, this particular bureaucrat held that honorable position “despite having been an enemy of our cause,” lamented the sub-inspector. Of course, any similarity of this case of official impunity with today’s reality is mere coincidence.

Let’s move on from the rascals and have a look at the rogues.

Rogues

El Vacavieja (Old Cow)

Let’s start with Antonio Palma, better known as “El Vacavieja,” a gentleman of wit and good humor from the Río Sonora region who, in the prohibition years, acted as assistant to the municipal president of Huépac. One day, the presidente said to Vacavieja: “Look, Antonio, I am going to ask you for much discretion in the commission that I am going to entrust you with. You know that General Calles issued a dry law for the entire state, but it has come to my attention that so-and-so may be selling bacanora under the table. I have orders to verify it and send him to the authorities.” Antonio listened intently as the mayor continued, “I’m going to give you 50 cents, and you buy the bacanora as if you don’t know anything. You have enough for a bottle, and you bring it to me. Do you understand?” “Of course, I do!” replied Vacavieja, amazed that his boss could actually loosen up since he had a reputation for being very stingy. The mayor ended with: “When I have the evidence in hand, I will initiate the prosecution against him.”

According to the Archivo General del Estado de Sonora, this method of policing — buying bacanora from suspected offenders and then presenting the purchase as evidence against them — was actually quite common during this time. Vacavieja set out in a rush to fulfill the wishes of the presidente municipal. Two hours later, he returned, red-eyed and wobbly, the presidente staring at him. “Patrón, it is not true that this man is selling mezcal. He offered me a few sips of some of it that he has for his personal use. What he did sell me, and for exactly fifty cents, was this boatload of acorns.” Vacavieja then showed the mayor a jar full of acorns that the alleged criminal had given to him for free.

Discouraged, the highest authority of the town was left without proof of the crime and had lost his money. Vacavieja had taken both the dough and the booze!

It is worth noting, however, that this story, collected by professor Terán, may contain an inaccuracy in stating that it was legal to possess bacanora for personal consumption. Archival documents that I have reviewed, dating from August 1915 to early December 1921, show that in fact no quantity of bacanora was permitted. On the other hand, I did find plenty of evidence that in 1922 it was nonetheless legal for personal consumption if one paid the authorities for a permit.

Such was, however, not the case for Miguel C. Valdéz, a Mexican of Chinese origin who, on March 16, 1922, declared in a Nogales court that, “the confiscated liquor [which he had possessed] was publicly purchased in the Offices of the Commercial Company, not [for the purposes of] trade…but for…personal use” (Archivo del Poder Judicial del Estado de Sonora, File 431, Document number 1).

El Mocho Valdéz

Even more famous than Vacavieja was Emilio “El Mocho” Valdéz, about whom I discovered in the writings of Mr. Rodolfo Rascón Valencia, a relative of mine and a magnificent chronicler of the Sierra.

Don Rodolfo told me that Valdéz was a resident of Huásabas who had lost his right hand in a fireworks explosion and also his left hand when a sugarcane mill turned it into “chorizo.” From then on, he was known as “El Mocho,” but he never stopped working, for he was not easily discouraged, “and could handle a pencil between his stumps as well as a pick and a shovel when working in the fields.” One day, El Mocho was carrying a shipment of booze along a backroad near Colonia Morelos, below Bavispe, when he ran into the so-called Acordada. Sonoran oral tradition holds that Los Acordada were a group of rural gunmen with a license to kill. To make matters worse, the Acordada were led by the fearsome Canuto Ortega, a famous hunter of bootleggers in the region.

Eventually, Ortega ran into El Mocho, who had a donkey loaded with “two barrels of mezcal, the 40-liter kind,” Rascón explained to me while holding a cup of black coffee.

“What’s up, Mocho? You sonofabitch, what do you have there?”

“You know, why do you have to be such a jerk about it?”

Ortega paid no heed to this remark, saying, “And where are the others?”

El Mocho looked at him, perplexed. “Which others?”

“The ones who helped you.”

“I did it myself. There were no others.”

Rascón told me that El Mocho had in fact harvested the agave and made the mezcal with no help from anyone else, working with just his two stumps.

“Ok, pull down his load,” Canuto shouted to the two officials who accompanied him, “and if he can’t load it back up by himself, we’re going to hang them [El Mocho and his donkey] by their armpits from that mesquite [over there].”

The skillful donkey then lowered himself down to Mocho’s level and began to carry him. Mocho tossed his rope over the packsaddle, using his two stumps with astonishing dexterity.

He then rolled up a barrel and laid it over the rigging, wedging it with a hat to keep it from rolling away. He quickly walked around to the other side and raised up the other barrel, reeling in the load with such mastery that it left the officers speechless. Finally, he situated the two barrels on each side of the rigging, tying the loop with his teeth and leaving the feared Canute in complete shock. Once Canuto recovered, he managed to spit, “Get out of here, Mocho, you bandit! And I don’t want to hear about you going around telling people that I was soft and didn’t hang you by your armpits.”

Los Chinos

According to Professor Irene Rios Figueroa, the photo above is taken from a place “15 kilometers away from the El Tigre mine, known as Los Chinos because of the trees of that same name [growing in the area]. A stream crosses Colonia Morelos road, at the intersection with the road from Esqueda. It is said that this used to be the Acordada’s favorite place to hang people who – guilty or not – were accused of cattle rustling, alcohol trafficking, robberies, etc..” (published on Rios Figueroa’s Facebook page, September 22, 2021).

The Persecuted

When reading the intriguing records of the Archivo General del Estado de Sonora (AGES), it becomes quite clear that the Sonoran government violated the rights of many citizens in order to enforce its moral crusade against alcohol use. Such was the case of Pancho Duarte, a “quiet resident” of Hermosillo, who, in a letter addressed to the governor on August 9, 1921, complained, “My home was assaulted at midnight last Tuesday, July 19, when police officers broke in to carry out a search ordered by the municipal president, looking for liquor that they did not find. As a zealous guardian of the order and tranquility of my honorable family, I firmly protested, trying to be reasonable and avoid violence. Still, they entered my house without any consideration, searching through everything and not finding what they were looking for but leaving fear and resentment among my sisters and my sick, elderly father.”

Merchants were also impacted and were forced to carry on with their businesses by any means possible, even if it meant selling bottles of alcohol to “customary drunkards crossing the city streets in a state of intoxication.” This is how the anti-drug inspectors assessed Mr. Leonardo Mirazo’s condition. He was sent to what is today known in Hermosillo as the Old Penitentiary for refusing to betray his source, Mr. Luis Cano, owner of the Boitica Nueva, located on Calle Serdán.

Things turned out somewhat better for our next character, a drinker, but one with money: the mythical “Gandarita,” whose real name was Francisco P. Gándara. Don Francisco was arrested on the night of April 5, 1921, for being a “scandalous drunk,” as noted on his prison record. That same night the city mayor released him by immediately paying the fine of twenty pesos, which surprised the governor because the offender was “a wealthy man with no problem paying the fines imposed on him.” The governor thereby concluded his scolding of the mayor of Hermosillo by saying, “I encourage you to apply with due rigor the corresponding penalties to all individuals apprehended for drunkenness, especially to those accused of scandals and misdemeanors.”

Ending the list of the persecuted in 1921 — the year which saw the ultimate demise of the dry law — we have the case of Los Nachos (The Ignacios) or El Vacilón. It all began with the arrest of Ignacio Jaime as he was leaving Ignacio Cajigas’s home on the night of August 18, 1921. Inspector Jesús R. Barreras caught him “carrying six bottles of prohibited liquor to the bar called El Vacilón, owned by Cajigas, and detained him for the said infraction in the State Penitentiary and in the custody of the authorities,” the inspector noted in his report. As in Gandarita’s case, Don Nacho Cajigas had to pay not twenty pesos in fines but 175 pesos in national currency [“oro nacional”] “as a donation to the “Cruz Gálvez” Schools. This is how Cajigas was released one day after the embarrassing events. (These four cases that make up the “Persecuted” section from folder 3415 of the Archivo General del Estado de Sonora.)

Lifting of the Dry Law

With the aroma of revolutionary gunpowder permeating Sonora’s battered economy, there seemed to be no end in sight for alcohol smuggling, which meant that large amounts of tax revenues remained out of the state’s reach. At the end of 1919, the end of the Dry Law began with the enactment of Law Number 6, which repealed the original Calles decree and opened the door once more to the legal “production, traffic and sale of beer, table wines, cider, and champagne” (Fernando Pesqueira, Leyes y Decretos del Estado de Sonora, 1917-1923, Universidad de Sonora, pp. 322 and 327). Although liquors were still prohibited (including whiskeys, cognacs, and mezcal, both tequila and bacanora) the extensive evidence tells us that the law was little more than a paper tiger since liquor still ran like a stream across the state of Sonora. On March 9, 1921, for instance, the provisional governor himself informed the Chief of the Fiscal Gendarmerie of Magdalena that in his jurisdiction, “the current laws on Intoxicating Beverages are violated every day, with the acquiescence of the authorities,” to which the recipient of the message, Lieutenant Colonel Sánchez, replied, “Here there is indeed too much tolerance on the part of the authorities, and with unheard-of cynicism, laws are systematically circumvented” (AGES, 3415).

Still, at the beginning of that same year, 1921, Don Plutarco, now Secretary of the Gobernación [Interior], stoked the “campaign against gamblers and alcohol users” in Sonora, addressing the new governor, Miguel H. Piña, in a telegram on January 1, whom he congratulated on his new position but also complained that, “I have not received my Christmas cards.” The new governor replied, “You can be sure that I will declare a relentless war against gamblers and drinkers, and as for the Christmas cards, I’m already booking a car in the Sudpacífico Railroad to deliver them to you” (AGES, 3412). (This “Christmas Cards” reference is most probably an unsubtle allusion to some kind of kick-back.)

By June, however, officials began to modify the current law, arguing that a fall in tax collection and a “paralysis of the copper mining industry due to the drop in the price of this metal” was to blame, as the governor explained to the state congress. In October, Law number 6 was issued and, in December, Law number 15, which contained the regulatory stipulations for the former. In both cases, it became more than clear that, “The production, trafficking, and sale of all kinds of intoxicating drinks is allowed across the state” (AGES, File 3412). These laws included, of course, bacanora. In short, it is only within the superficial collective imagination and the work of some historians that we had a continuous “ban [on liquor] that spanned from 1915 to 1992…” We will address that myth at another time. For now, please have a toast with some tasty Sonoran bacanora!